Setting up your playground

This exercise will load sample data as well as some indexes and queries. You’ll

see this run for a bit on your screen. Wait until you see postgres=# and then

continue.

Cache Hit

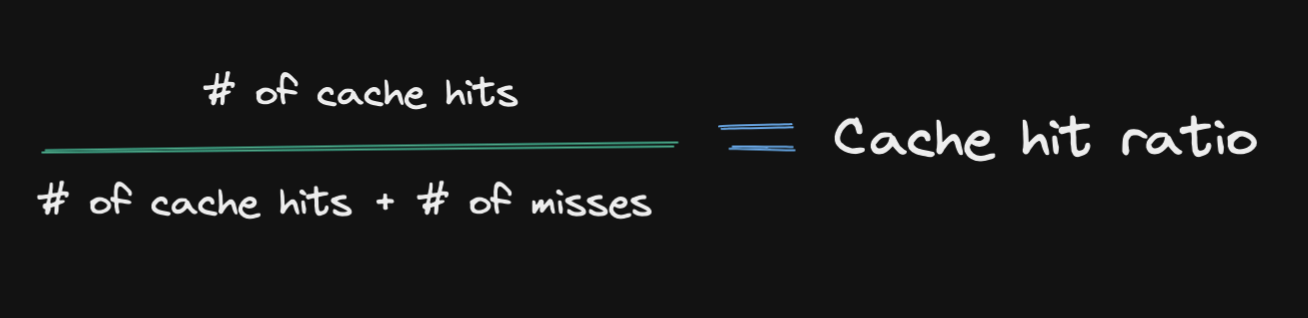

Postgres generally tries to keep the data you access most often in the cache. Cache hit ratio measures how many content requests a cache is able to handle compared to how many requests it receives. A cache hit is a request that is successfully handled and a miss is one that is not. A miss will go beyond the cache to the base machine to fulfill the request.

So if you have 100 cache hits and 2 misses, you’ll have a cache hit ratio of 100/102 which equals 98%.

Find your cache hit with:

SELECT

sum(heap_blks_read) as heap_read,

sum(heap_blks_hit) as heap_hit,

sum(heap_blks_hit) / (sum(heap_blks_hit) + sum(heap_blks_read)) as ratio

FROM

pg_statio_user_tables;

For normal operations of Postgres and performance, you’ll want to have your Postgres cache hit ratio about 99%.

If you see your cache hit ratio below that, you probably need to look at moving to an instance with larger memory.

Index Usage

Adding indexes to your database can be critical to query and application performance. Indexes are particularly valuable across large tables.

Here is a query to find your table sizes in rows and % of time the index is used, versus a non-index read.

SELECT

relname,

100 * idx_scan / (seq_scan + idx_scan) percent_of_times_index_used,

n_live_tup rows_in_table

FROM

pg_stat_user_tables

WHERE

seq_scan + idx_scan > 0

ORDER BY

n_live_tup DESC;

In general, you are looking for 99%+ on tables larger than 10,000 rows. If you see a table larger than 10,000 with no or low index usage, that’s your best bet on where to start with adding an index.

A couple notes about creating indexes:

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLYwill allow you to build your index in the background and not hold a lock on your tablemaintenance_work_memspecifies how much memory is used for creating indexes and other background work like vacuum. The default value is 64 MB. Consider setting this higher when creating large indexes in the background.

Index Cache Hit Rate

If you’re interested in how many of your indexes are within your cache you can run:

SELECT

sum(idx_blks_read) as idx_read,

sum(idx_blks_hit) as idx_hit,

(sum(idx_blks_hit) - sum(idx_blks_read)) / sum(idx_blks_hit) as ratio

FROM

pg_statio_user_indexes;

Bloat

Postgres has a special way that it handles updated or deleted statements. Even

though data is removed, the actual storage space of that data is retained until

the database is vacuumed. If you have a busy database with a lot of delete

statements, bloat can leave a lot of unused space in your database and an impact

performance if not handled.

There is a query to see bloat.

SELECT

current_database(), schemaname, tablename, /*reltuples::bigint, relpages::bigint, otta,*/

ROUND((CASE WHEN otta=0 THEN 0.0 ELSE sml.relpages::float/otta END)::numeric,1) AS tbloat,

CASE WHEN relpages < otta THEN 0 ELSE bs*(sml.relpages-otta)::BIGINT END AS wastedbytes,

iname, /*ituples::bigint, ipages::bigint, iotta,*/

ROUND((CASE WHEN iotta=0 OR ipages=0 THEN 0.0 ELSE ipages::float/iotta END)::numeric,1) AS ibloat,

CASE WHEN ipages < iotta THEN 0 ELSE bs*(ipages-iotta) END AS wastedibytes

FROM (

SELECT

schemaname, tablename, cc.reltuples, cc.relpages, bs,

CEIL((cc.reltuples*((datahdr+ma-

(CASE WHEN datahdr%ma=0 THEN ma ELSE datahdr%ma END))+nullhdr2+4))/(bs-20::float)) AS otta,

COALESCE(c2.relname,'?') AS iname, COALESCE(c2.reltuples,0) AS ituples, COALESCE(c2.relpages,0) AS ipages,

COALESCE(CEIL((c2.reltuples*(datahdr-12))/(bs-20::float)),0) AS iotta /* very rough approximation, assumes all cols */

FROM (

SELECT

ma,bs,schemaname,tablename,

(datawidth+(hdr+ma-(case when hdr%ma=0 THEN ma ELSE hdr%ma END)))::numeric AS datahdr,

(maxfracsum*(nullhdr+ma-(case when nullhdr%ma=0 THEN ma ELSE nullhdr%ma END))) AS nullhdr2

FROM (

SELECT

schemaname, tablename, hdr, ma, bs,

SUM((1-null_frac)*avg_width) AS datawidth,

MAX(null_frac) AS maxfracsum,

hdr+(

SELECT 1+count(*)/8

FROM pg_stats s2

WHERE null_frac<>0 AND s2.schemaname = s.schemaname AND s2.tablename = s.tablename

) AS nullhdr

FROM pg_stats s, (

SELECT

(SELECT current_setting('block_size')::numeric) AS bs,

CASE WHEN substring(v,12,3) IN ('8.0','8.1','8.2') THEN 27 ELSE 23 END AS hdr,

CASE WHEN v ~ 'mingw32' THEN 8 ELSE 4 END AS ma

FROM (SELECT version() AS v) AS foo

) AS constants

GROUP BY 1,2,3,4,5

) AS foo

) AS rs

JOIN pg_class cc ON cc.relname = rs.tablename

JOIN pg_namespace nn ON cc.relnamespace = nn.oid AND nn.nspname = rs.schemaname AND nn.nspname <> 'information_schema'

LEFT JOIN pg_index i ON indrelid = cc.oid

LEFT JOIN pg_class c2 ON c2.oid = i.indexrelid

) AS sml

ORDER BY wastedbytes DESC;

wastedbytes and index wasted bytes wastedibyteswill show you if you have any

major bloat concerns.

Vacuum

Bloat can be reduced by vacuuming your database. Postgres will come with autovacuum turned on and enabled by default. You can make see the last time autovacuum ran with this query:

SELECT relname, last_vacuum, last_autovacuum FROM pg_stat_user_tables;

Vacuum will only let the database reuse this space. It doesn’t magically reduce

the space that your database is using - if you’re looking at storage metrics. If

you’ve run into a storage issue and you need to delete data, look into the

vacuumdb utility and proceed with caution.